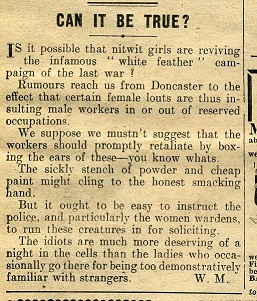

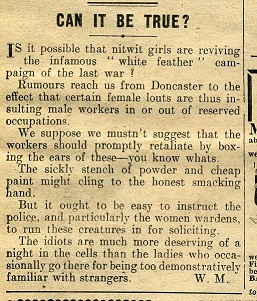

Although the infamous white feather campaign – the vile practice of women handing out white feathers to men in civilian clothing in an effort to shame them into enlisting – is associated with the First World War, during which it was a widespread phenomenon (and encouraged by leading feminists such as Christabel Pankhurst), there is evidence that some women tried to resurrect the practice in the early years of the Second World War. The following is an editorial from the Daily Mirror dated April 30th 1940 :

The antics of the feminist White Feather campaigners became so intense and feared during the course of the First World War that the government began to issue silver badges for brave soldiers who had been honourably discharged through wounds or sickness in order for them to demonstrate that they were veterans when wearing civilian clothing and hence spare them from the possible wrath of the feminist cowards.

When the Second World War broke out, there was sufficient concern that the White Feather campaign would repeat itself again that the government deemed it necessary to revive the Silver Badge idea, under the form of ‘the King’s Badge’.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silver_War_Badge

The Silver War Badge was issued in the United Kingdom to service personnel who had been honourably discharged due to wounds or sickness during World War I. The badge, sometimes known as the Discharge Badge, Wound Badge or Services Rendered Badge, was first issued in September 1916, along with an official certificate of entitlement.

The sterling silver lapel badge was intended to be worn in civilian clothes. It had been the practice of some women to present white feathers to apparently able-bodied young men who were not wearing the King’s uniform. The badge was to be worn on the right breast while in civilian dress, it was forbidden to wear on a military uniform.

The badge bears the royal cipher of GRI (for Georgius Rex Imperator; George, King and Emperor) and around the rim “For King and Empire; Services Rendered”. Each badge was uniquely numbered on the reverse. The War Office made it known that they would not replace Silver War Badges if they went missing, however if one was handed into a police station then it would be returned to the War Office. If the original recipient could be traced at his or her discharge address then the badge would be returned.

A very similar award, known as the King’s Badge, was issued in World War II. Although each was accompanied by a certificate, issues of this latter award were not numbered.

It was common for men who had been given the White Feather by feminists in the First World War to either kill themselves through shame, or else to immediately sign up and face proabable death, even if they were suffering from genuine disability, had already fought and been traumatised, or even if they were underage children.

A man describes his grandfather’s experience of being a victim of the White Feather campaigners :

After reading, in quick succession, four books about the men who fought the war, I took out a box of flimsy, yellowing letters, and tried yet again to imagine what my grandfather went through.

He had three small daughters, which saved him from conscription, and his attempt to volunteer was turned down in 1914 because he was short-sighted. But in 1916, as he walked home to south London from his office, a woman gave him a white feather (an emblem of cowardice). He enlisted the next day. By that time, they cared nothing for short sight. They just wanted a body to stop a shell, which Rifleman James Cutmore duly did in February 1918, dying of his wounds on March 28.

My mother was nine, and never got over it. In her last years, in the 1980s, her once fine brain so crippled by dementia that she could not remember the names of her children, she could still remember his dreadful, useless death. She could still talk of his last leave, when he was so shellshocked he could hardly speak and my grandmother ironed his uniform every day in the vain hope of killing the lice. She treasured his letters from the front, as well as information about his brothers who also died.

She blamed the politicians. She blamed the generation that sent him to war. She was with Kipling: “If any question why we died, / Tell them, because our fathers lied.” She was with Sassoon: “If I were fierce, and bald, and short of breath / I’d live with scarlet majors at the Base, / And speed glum heroes up the line to death … And when the war is done and youth stone dead / I’d toddle safely home and die – in bed.”

But most of all, she blamed that unknown woman who gave him a white feather, and the thousands of brittle, self-righteous women all over the country who had done the same. And there were thousands of them, as Will Ellsworth-Jones makes clear in his fascinating account of a group of conscientious objectors, We Will Not Fight. After the war, Virginia Woolf suggested there were only 50 or 60 white feathers handed out, but this was nonsense – as Ellsworth-Jones’s diligent research shows.

Some of his stories still have the power to make the reader angry. A 15-year-old boy lied about his age to get into the army in 1914. He was in the retreat from Mons, the Battle of the Marne and the first Battle of Ypres, before he caught a fever and was sent home. Walking across Putney Bridge, four girls gave him white feathers. “I explained to them that I had been in the army and been discharged, and I was still only 16. Several people had collected around the girls and there was giggling, and I felt most uncomfortable and … very humiliated.” He walked straight into the nearest recruiting office and rejoined the army.

Since I published this article in 2012, I did some further research into the White Feather campaign in World War II, using historical newspaper archives. I was surprised to find that the practice of handing out white feathers was even more widespread in the Second World War than previously assumed, and tragically, it did lead to suicides, including at least two teenage boys :

White Feathers During World War II Caused the Suicides of Two Teenage Boys